Murcado da Balburdia

Murcado da Balbúrdia is one of my ongoing projects. In it I aim at an uncompromised, unbiased gaze, which took me to Alte, a village I have known since my childhood, in Southern Portugal.

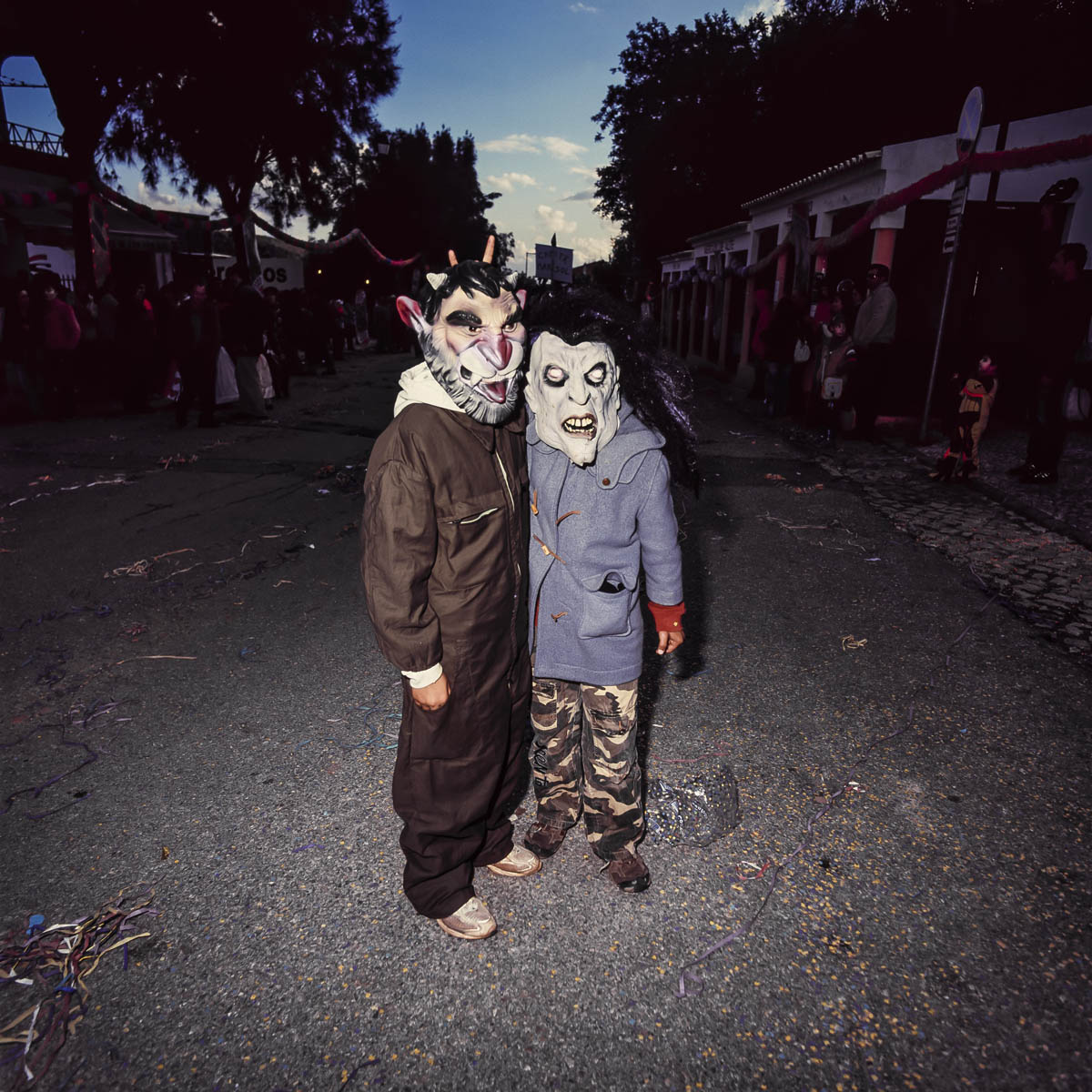

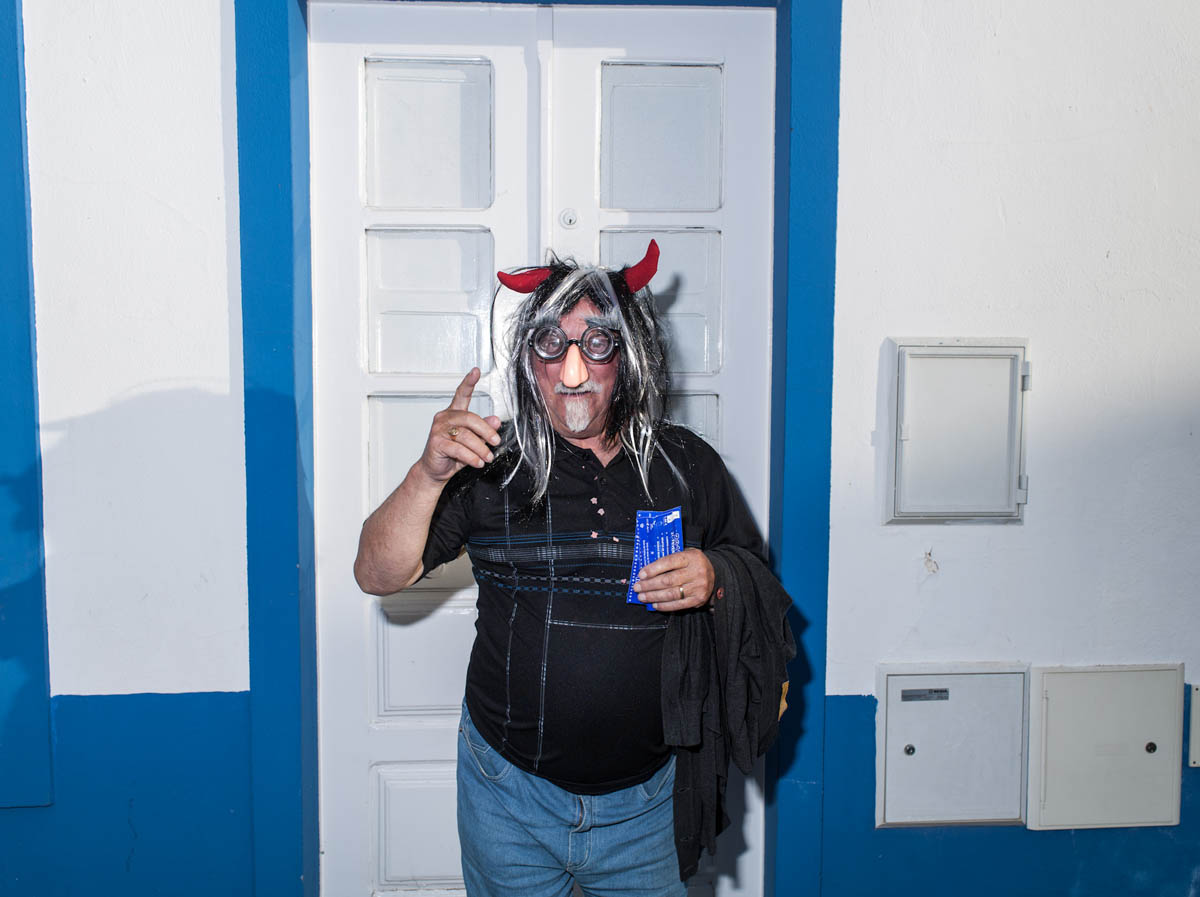

In 2007 I visited Alte during Carnival, summoned by folk traditions of the season. I was struck to see the intensity with which the locals lived those traditions linked to Carnival: the masks, tricks, fantasy, comedy, all was enacted autonomously, with no glamour or ambition whatsoever beside the sheer will to get together in a small country town. Carnival was not my sole interest when I went to Alte in this period; instead, all form of celebration and social interaction attracted me for being so rare in places like these, and for bringing up very singular moments of socialization.

Excerpts from the Text of curator Nuno Faria:

(...) The panorama shown in this exhibition begs the conclusion that Vasco Célio is less moved by simple curiosity or by the appeal of celebration than by a quest for identity. He is in search of the identity of the place, the identity of a community - ultimately, his search is for the identity of himself as an individual and as an author.

When accomplished according to an authorial, self-reflexive logic, the practice of photography is a research equivalent to that of a scientific, or academic study.

(...) In “Murcado da Balbúrdia” – the name keeps the original misspelling represented in one of the photographs – we can observe a gallery of more or less bizarre characters, vague caricatures who wander anonymously among a scenario of unique traits. In this series Vasco Célio is practicing different modalities of photographic discipline: from individual and group portrait to the uncanny scene, ambiguously staged, through images clearly detaching themselves from the original context via the perspective of the gaze, or via a deliberate mask play of face annulment, which underlines the autonomy of the image vis-a-vis a supposedly documentable reality.

(...) Usually, photography disarms and deceives: it is a mimesis of reality and it is also a constructed reality, a framed shot, a point of view. What Vasco Célio is proposing through this most complex of disciplines of the image is a vision of the world we live: his intention is to open up the world to us, to widen up the perception we have of ourselves and of others, by transforming maximum familiarity into the radical uncanny, and vice-versa. Such is the sortilege of photography.